Below is a transcript of my comments for this series. Click here for a video of the remarks used. For the whole series (which I recommend) click here.

What makes the Russian war against Ukraine different from other conflicts in Europe since World War II?

This is a crisis caused by a Great Power (the Russian Federation) invading a neighboring state in order to not only overthrow its government but to purge (“de-nazify”) its elites, and annex large parts of its territory. This war is an enormous land grab, the largest we have seen on the European continent since the time of Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union.

Territorial revanchism is a messianic form of geopolitics. Europe did see, in the early 1990s, the emergence of a revanchist geopolitics in Serbia, under Slobodan Milosevic, as the Yugoslav Federation (Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia) disintegrated. The idea is to ‘take back’ or ‘recover’ territories that radical nationalists believe primordially ‘belong to’ the core state. So Serbia sponsored separatist militias in Croatia and Bosnia in order to create a new territorial and demographic order.

Territorial revanchism is an attack on what exists – the real — in the name of what should exist –a mythic ideal. Actually existing places, and communities, need to be destroyed in order to create what the leader deems to be the desirable arrangement of territories and borders, the ‘natural order,’ the ‘eternal order.’ The contradiction is obvious here: violent force has to be used to make that which is held to be ‘natural’ and ‘eternal.’

This is what we saw in the Bosnian war of 1992-1995, a conflict that gave the world the phrase ‘ethnic cleansing.’ A not dissimilar process, one with euphemistic phrases like ‘filtration’ and ‘ethnic rehabilitation’ (sic), is occurring in the occupied territories of Ukraine today.

Putin is, in many ways, following in the footsteps of Milosevic. His war is a war against actually existing Ukraine, and Ukrainians, in the name of historic myths. He sees himself correcting historic injustices and mistakes. It is also a deeply self-serving war, a war in which he is the hero of his own violently imposed drama. Putin imagines himself a man of iron (Stalin) fighting once more a Great Patriotic War against fascist enemies at the gate.

Tragically, Russian revanchism in Ukraine is on a much greater scale than anything Serbia, and its proxies, were able to violently impose across Bosnia-Herzegovina. Before February 2022, Russia controlled about 7% of the territory of Ukraine, annexing Crimea right away in March 2014 and controlling separatist groups in the Donbas. After this second invasion, Russia seized more than a quarter of Ukrainian territory (27%) before determined Ukrainian resistance drove it back. It currently occupies roughly 18% of Ukraine. In September 2022 Russia unilaterally annexed four regions of Ukraine beyond Crimea: Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia and Kherson, even though it does not fully control the territory of these Ukrainian oblasts. Nevertheless, the Russian state now presents these regions as integral parts of the Russian territorial landmass. Contemporary maps across Russia – from road maps to school atlases — now display the regions as part of Russia, just like Crimea.

- What is the forced displacement situation in Ukraine? How does it compare to forced displacement situations in other countries?

Russia’s war against Ukraine was a war against places as they existed, and against the ordinary Ukrainians living there. Initially, Russia thought that Ukrainians would welcome their invasion as a ‘liberation.’ When they quickly realized this was far from the case, they openly attacked civilian populations in the places they wanted to control. The goal was to terrorize the population, forcing people to leave. Filtration camps or worse were faced by many. People in captured regions have to submit to forced Russification, everything from mundane things like joining Russian mobile phone networks to more official steps like taking Russian passports.

The overall aim has been to seize territories more than liberate people, to terrorize and displace, then occupy and build a ‘new Russia,’ upon seized Ukrainian territory. They terrorized the population of Mariupol – killing them and driving them from the city – and then sought to turn it into a model reconstruction, in effect a modern-day Potemkin Village.

Russia’s invasion has generated the largest, and fastest, migration crisis in Europe since the Second World War. To date Russia’s war against Ukraine has generated approximately 6.5 million refugees, people who have left the country in search of safety. The majority of these are women and children, as well as the elderly, with most being accommodated in states across the European Union. Poland deserves special commendation for accommodating more than a million Ukrainians at the outset. Germany now host the largest number of Ukrainians in Europe while Czechia hosts the largest numbers per capita. My own home country of Ireland currently accommodates more than 104,000 Ukrainian refugees. Since the initial wave of displacement there has been a pendulum of migration — brief returns and then departures – by Ukrainians.

There are an estimated 3.7 million internally displaced persons currently living within Ukraine. The majority of the internally displaced remain in frontline regions: Zaporizhzhia, Dnipro and Kharkiv as well as the urban regions of Kyiv and Odessa. It also needs to be remembered that millions of Ukrainians depend every day upon humanitarian assistance – including psychosocial services — to survive and hold it together. This figure will rise to 14.6 million in 2024 according to the UNHCR.

In total, nearly one in four Ukrainians has been displaced by Russia’s war. Half of Bosnia’s population was displaced during that awful war. Ukraine has ten times the population of Bosnia.

This war is violent demographic engineering, a purposeful breaking of places and communities, a deconstruction of a country, a separation of people from land.

- 10 million + people.

- Thousands of homes, communities, territories destroyed.

- Thousands of kilometers poisoned by remnant munitions and landmines.

These enormous statistics can numb us to the fact that there are stories of stress, suffering and pain behind every single one of these figures.

- How has Russia’s invasion reshaped Ukrainian society and societal views (eg social, political, economic, etc.)?

Russia’s invasions, both in 2014 and 2022, have radicalized Ukrainian society and identity. Many Ukrainians were not supportive of the Euromaidan protests and subsequent change of government in March 2014. But Russia’s invasion of Crimea and subversion of the Donbas provoked a backlash against Vladimir Putin and Russia that had lasting effects. In taking Crimea, Putin lost Ukraine. More and more Ukrainians began to identify with a civic Ukrainian identity, as opposed to a local or ethnic identity. There was greater societal consensus on the need for Ukraine to orient itself toward the European Union (this was facilitated by the fact that the most pro-Russia regions of Ukraine were removed from its political life by Russian occupation). Russia’s efforts to block the capacity of Ukraine to make a ‘civilizational choice’ for Europe through the Minsk process were rejected.

The February 2022 invasion greatly accelerated the process of cultural and linguistic Ukrainianization within the country’s population. It was impossible to still foster ideals about Russia, except for older deeply Sovietized groups. More Ukrainians started speaking Ukrainian, more rejected Russian-Soviet memory politics, and more and more repudiated Russian cultural levers of influence in Ukraine (like the Moscow Patriarchy of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church). The state of emergency created by the war and media controls – media deemed ‘pro-Russia’ was banned – have consolidated this but it is not a top-down creation. Rather it is an identity formed in everyday opposition to Russia’s invasion and all who support it.

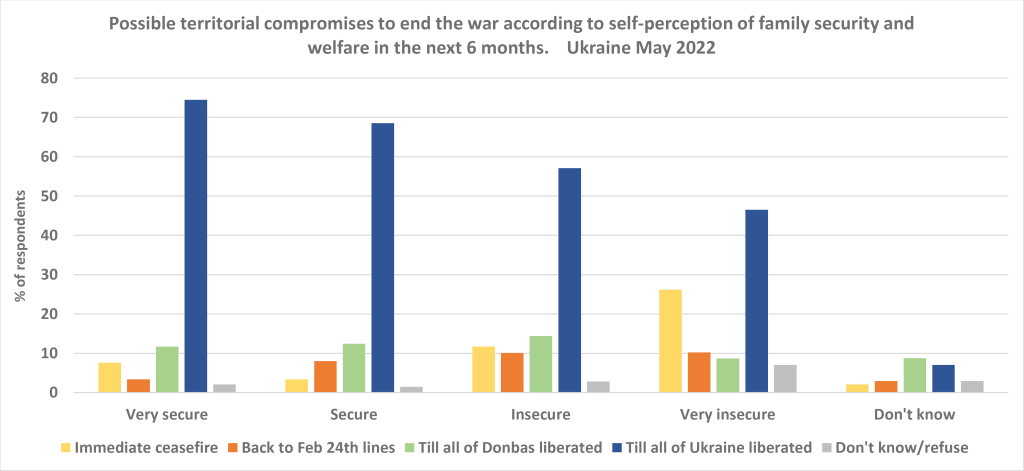

There is now widespread societal consensus, to the extent that wartime polling is reliable, around Ukraine’s Euro-Atlantic geopolitical orientation, with strong majorities supporting its membership in the European Union and NATO. But we must remember that wartime polling does not include areas occupied by Russian and those forced into exile by the war.

Instead of seeing societal change in terms of geopolitics and identity, it is important to remember that, first and foremost, Ukrainian society is now a nation of loss, pain and suffering. Thousands have been wounded and thousands now carry trauma and mental wounds from this war. This will exercise a profound effect on post-war Ukraine and indeed on all Ukrainian communities worldwide.

- To what extent is the Russia-Ukraine war impacting territorial disputes in the Balkans, the South Caucasus, and elsewhere?

Russia has re-introduced war as state policy to European political life. Its invasion of Ukraine has had global, indeed planetary, impacts as well as continental and regional one, across former Communist lands.

First, in the decisive decade of the fight against climate change, Russia’s invasion has thwarted any hope of concerted collective effort by the great powers, in the near term, to prohibit the emissions that drive “global warming” (better described as dangerous heating). Hydrocarbons make it possible for Putin to pursue his territorial fantasies. Europe’s effort to wean itself off Russian oil and gas is certainly positive, but the invasion has stimulated natural gas infrastructure investments that ‘lock in’ decades of future emissions. Countries beyond Europe continue to buy Russian oil. Russia, for example, had a record $37 billion in crude oil sales to India last year. Climate change will be the greatest threat to the territorial integrity of states in the future. This war has accelerated that outcome.

Second, Russia’s invasion had an initial sobering effect on rising tensions in the Balkans, particularly in Bosnia. Subsequently, though, the war has deepened divides in the region, between Republika Srpska’s leadership, Bosnian state officials and EU officials, and between Serbia and Kosovo. Illiberal political forces across Europe, and indeed the world, have taken inspiration from Putin’s challenge to the liberal hegemony of Western powers.

Third, it should be recalled that Russia’s initial invasion plan suggested it hoped to drive all the way to Transnistria, in other words, to invade Moldova as well as Ukraine. Moldova is a somewhat neglected second frontline of the Russia-West divide. Russian supported Transnistria still receives subsidized Russian natural gas via Ukraine. Ukraine may end that link this year.

Fourth, Russia’s preoccupation with Ukraine, and the EU’s need to diversify its natural gas supply, created an opportunity for Azerbaijan to squeeze the Armenian population of Karabakh into submission. After a cynical blockade in 2023, Azerbaijan’s army used military force to terrorize the population in September 2023 into fleeing the enclave, ending the centuries long presence of Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh. The impact of this territorial reversal on Armenia is profound. Indeed, it is not clear that the Azerbaijan-Armenian territorial conflict is really over.

This awful war has worked its way into politics and everyday life across the globe. It’s a significant issue now in American domestic politics and in demagogic politics around immigration in European politics. We can only hope that we’re not marking a third anniversary of the war next year but talking instead about reconstruction and peace. But the current situation is grim for Ukraine and its people. They deserve our help.